Does any human art compare with the spectacle of autumn countryside?

Does any human art compare with the spectacle of autumn in the countryside? Lose yourself amid the burnished glory of rosehips and the crunch of acorns

Every season has its quintessential location. Who does not want to be beside the sea in summer, or standing on a mountain in the freshening breeze of spring? As for winter, where better to be than a metropolis, with the bright lights of the big city reflecting off its wet pavements.

But come autumn the mind drifts inevitably to the countryside: the woods, orchards and lanes of Britain where the trees and bushes become heavy with fruit, and the rich earth erupts with mushrooms.

There, birds sing in the seasons. Just as the cuckoo announces spring, so the fieldfare is the herald of autumn.

When I walked through a wood in Herefordshire this week, I heard the raucous chacking of these colourful members of the thrush family as they provisioned themselves on windfall pears in an orchard on the hillside.

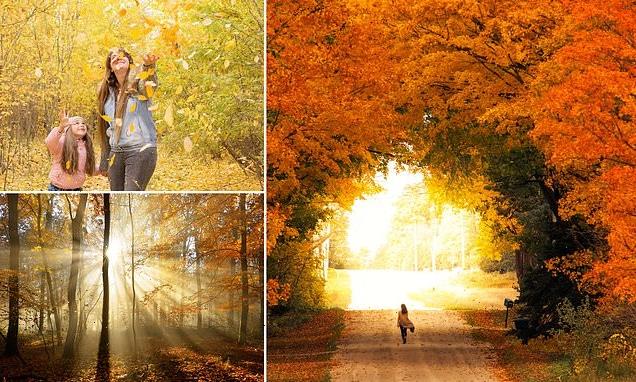

Forget politics, enjoy the autumn colours: Soft dappled light filters through the canopy to illiminate the leaves, tree trunks and forest floor which is covered in fallen autumnal leaves

In the foreground a small path leads through the forest, it too is covered in leaves and sunlight. Orange coloured leaves cling on to a tree during autumn. The large tree is surrounded by coniferous pines and larch

A woman walks through an opening between two large maple trees

And I witnessed autumn in the beginning of its glory, with the leaves of the trees ‘on the turn’.

Does any human art compare with the spectacle of the countryside in autumn? When the hedges of the lanes shimmer in gold and the wood flickers with all the reds of flame.

An oak leaf had alchemised into the colour of copper, and enough foliage had dropped and begun rotting to produce that characteristic spicy odour of autumn, a scent reminiscent of incense.

A wreath of mist lay low around the trees as a cock pheasant picked its way through the carpet of leaves in the manner of a fastidious bishop heading a procession.

The sky above was that clear, cold blue you get at this time of year, and under my feet the fallen acorns from the statuesque oak trees popped and crackled.

This air of abundance is not confined to my local woodland. Up and down the country, trees groan with fruit, conkers from horse chestnuts carpet the ground, and gardeners report a profusion of everything from plums to walnuts.

This remarkable plenitude can be attributed to the freak weather we have experienced this year: a wet spring followed by summer heatwaves.

Drought-hit trees and bushes put all their efforts into producing more seeds in order to create another generation.

The oaks in my local wood have been working particularly hard. Indeed, it’s been a ‘mast year’ for acorns — meaning we have a bumper crop — something that occurs every three to five years.

Other British trees have mast years, notably beech. However, nature is capricious, and while there are reports of beech mast all over the UK and Ireland, the Herefordshire beech tree I think of as mine — one can get oddly fond of particular trees — has produced a mere few husks, and even these had shrivelled kernels.

Autumn morning at Tarn Hows in the Lake District National Park, Cumbria

Native, wild European hedgehog curled into a ball, preparing for hibernation, is pictured. Facing forward in colourful Autumn or Fall leaves

As the light faded on a still autumn afternoon, I spotted a jay enjoying the acorn bonanza. It flew down, filled its beak, then took off with its white rump flashing, lightbulb-like, to add to its cache.

This secret larder, dug into the woodland floor or pecked out of the end of a rotten bough, enables the bird to survive the hard times of winter.

Elsewhere, a grey squirrel sat on its haunches, masticating furiously as it took full advantage of nature’s bounty.

My pigs are allowed into the wood at this time of year to fill their snouts with acorns, an autumn farming rite known as ‘pannage’.

Once upon a time it enabled the survival of the porcine economy. My mother’s family held pannage rights in the Golden Valley of Herefordshire until the 1600s, a matter quite literally worth fighting over, according to contemporaneous court records.

A mother and daughter frolic among the falling leaves in a city park

A red deer stag bellows in Bushy Park deer park, London. Red and fallow deer still roam freely throughout the park, just as they did when Henry VIII used to hunt in the park

Gray cranes (Grus grus) fly to their roosting site at sunset above the lake

But fewer and fewer of us practise the old ways, and pannage is a tradition common only in the New Forest today.

There is excitement, too, in autumn’s frost; the way it anticipates the thrill of winter, without the actual drudge of melting snow or February’s ceaseless rain.

And it is the white kiss of frost which sweetens sloes, the plum-like fruit of blackthorn and the crucial ingredient of that country Christmas classic, sloe gin.

For in this season we behave very much as the birds and beasts do. Just as the jay prepares its larder and the squirrel puts on fat by feasting on acorns, we humans busy ourselves making bramble jelly and apple chutney, and gathering chestnuts to roast over an open fire.

It’s all about accumulating what gets you through the winter. There is something pleasantly prehistoric in picking hazelnuts from the hedge (if you can beat the squirrels to them) as our Stone Age ancestors did.

Indeed, until the 1950s, Britain was dependent on collecting the wild foods of autumn. During World War II, when U-boat activity menaced the nation’s naval supply lines, the Ministry of Food even produced a pamphlet entitled ‘Hedgerow Harvest’, and dispatched non-combatants to pick nuts and berries

The men from the Ministry were on to something. One of their top picks of the autumn crop was the rosehip, the scarlet fruit of the dog rose, Rosa canina. If, in these inflationary days, you are concerned over the cost of supermarket ‘superfoods’ from exotic jungles, worry not.

The Glenfinnan Viaduct is a railway viaduct on the West Highland Line in Glenfinnan, Inverness-shire

Sunny weather in autumn park in the afternoon. The leaves lie on the ground of a deciduous forest of beech trees illuminated by sunbeams

The rosehip contains 426mg of vitamin C per 100g . . . the açai berry from the Amazon a paltry 9.1mg.

The dog rose is everywhere in Britain below the tree line, and this year the hips are the largest I can recall. In the hedge on the lane they hang as tempting as rubies.

The hawthorn trees were also laden with fruit, and the sight of its blood-red berries recalled the venerable Scottish saying ‘Mony haws, mony snaws’ — many haws, many snows.

An old rowan tree, upright despite the wind and years, was festooned with scarlet berries — another portent in folklore of a cold, hard winter to come.

My walk was made that much nicer by the tart scent of wild crab apples as I picked sufficient to make a crab apple jelly. How much more pleasant to forage than to battle a trolley down the supermarket aisles.

Food and drink for free, what is not to like about autumn’s generosity? And it did not stop with the rosehip. Down in the bronze leaf-litter of the forest floor, I found the fungi-foragers’ grail: the cep mushroom, also known to chefs as ‘porcini’.

The bursting of Boletus edulis through the woodland floor is as certain a sign of autumn as the landing of the fieldfare.

Autumn colours are reflected in the water at Buttermere in the Lake District, Cumbria

View towards St. James Park in London during autumn season with golden trees and sunshine

I cut ten of the ceps encouraged into existence by the moist mist, and left a similar number standing — a tithe for nature.

Ceps are beloved by invertebrates and rodents alike, as well as gastronomes, and, while they may top the menu, 20 other edible mushrooms emerge in the autumn, which is fungi-time in these isles.

By then it was owl-light, as the darkness drew in.

This weekend, the night sky will be studded with diamante-stars, and shot across by comets, as an Orionid meteor shower lights up October’s night sky.

As I turned for home, through the chill air came the barking of a fallow deer buck. Then the thump of bone on bone. Two bucks were locking antlers. Autumn is the rutting season, mating time.

It may seem like a period of death and decay — the Americans even refer to the season as ‘The Fall’ — but, if you think about it, autumn is also the beginning of things, the start of life.

Source: Read Full Article