Cancer warnings could be coming to wine bottle and beer can labels

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

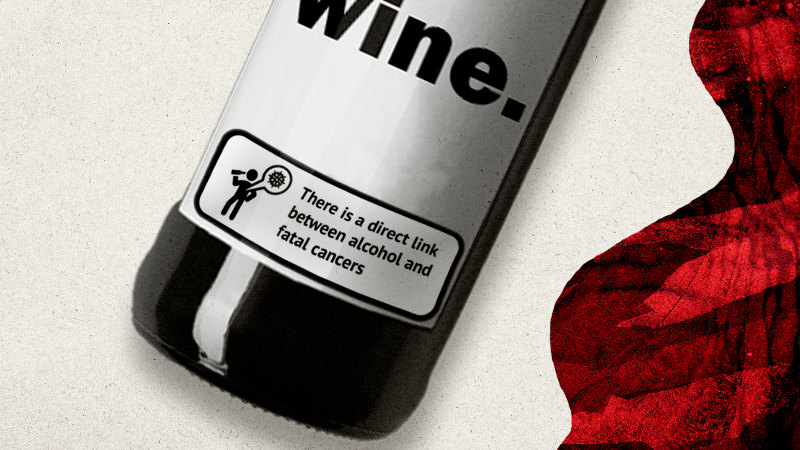

Bottles of wine and beer cans could soon be slapped with health warning labels similar to cigarette packets if the government heeds calls from national health groups.

The federal government is seeking advice on options to raise public awareness about alcohol harm as doctors’ groups launch a bid for cancer and other health warnings to be placed on all alcoholic beverages.

An artist’s impression of what future alcohol warning labels could look like.Credit: Aresna Villanueva

The Australian Medical Association (AMA) has joined the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE) in calling for alcohol producers to be forced to print labels on bottles, cans and casks warning of the risk of liver disease, cancer, heart disease, poor mental health, injury and alcohol poisoning.

In comments that are likely to worry the alcohol industry, the federal minister responsible for food and beverage labelling, Ged Kearney, said that she had sought advice from her department on options for raising consumer awareness about the harms associated with alcohol.

It is expected the advice will canvas new warning labels.

“The Australian government recognises the importance of labelling to raise consumer awareness of, and seek to prevent, alcohol-related harms,” said Kearney, the assistant minister for health and aged care.

Dylan Allen, who died from alcohol-induced hepatitis in 2022. He is pictured here, aged four, sitting on the kitchen bench.

The warning label campaign is supported by NSW woman Rachel Allen, whose son Dylan died last year at the age of 26, from alcohol-induced hepatitis, an inflammation of the liver.

The young man, an animal lover who was described by his mother as clever and informed about international politics, had been drinking up to five litres of cask wine a day.

Allen said in a statement provided by FARE that her son said before he died that if he could leave any legacy, it would be health warning labels on alcohol.

She wants products to carry labels that include photographs showing the harm alcohol can cause.

“I hope that a day will come when I could even volunteer to share pictures of Dylan before his death, when he was jaundiced… This would show the devastating impact that alcohol can have.”

Alcohol has long been a celebrated and intractable part of the nation’s culture. Last year, new prime minister Anthony Albanese was cheered on by revellers as he skolled a beer at a concert.

However, alcohol is also linked to more deaths in Australia than every illicit drug combined, attributed to about 6500 deaths each year, including hundreds of cases of breast, bowel and liver cancer.

“Alcohol has been so embedded in our culture, and the risks are underestimated significantly,” said RACGP president Dr Nicole Higgins.

Dylan Allen on Christmas Day in 2021.

“[It causes] cancer. The impact on mental health… it’s a huge risk factor for heart disease. And many of our injuries that happen, especially with our young people, are alcohol-related.”

FARE has argued warning labels would be overwhelmingly supported by Australians, citing its commissioned poll of 1004 Australians showing 78 per cent in favour of the measure. Among those Australians who backed the warnings, support was highest for labels about liver disease, at 91.2 per cent, and lowest for cancer warnings, at 54.5 per cent.

Alcohol was estimated to cause 1800 liver, bowel, breast and oesophageal cancer deaths each year, and more than 400 chronic liver disease deaths in an 2018 analysis by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

“We know the harm alcohol does to people’s health. Self-regulation and voluntary codes aren’t working,” said AMA president Professor Steve Robson.

The call to mandate alcohol warning labels comes soon after Ireland enacted laws requiring alcoholic drinks be labelled with health warnings and information, including calorie content and the risk of cancer and liver disease, from 2026.

It also follows Australia’s introduction of mandatory pregnancy warning labels in August, following more than two decades of campaigning and a three-year transition period.

A spokeswoman for Alcohol Beverages Australia, which represents drinks manufacturers, argued against the further health warning labels, saying “the issue of health data is complex and can’t be reduced to a label”.

“Warning labels on alcohol products is not government policy – instead safe drinking guidelines are issued for the community. Long-term trend reductions in consumption and moderation is well established in Australia including among youth,” she said.

“There are decades of research showing improvements in cardiovascular health, type 2 diabetes and dementia through light to moderate consumption.”

The World Health Organisation, however, said there was no safe amount of alcohol, or proven benefits that weren’t offset by harms.

FARE chief executive Caterina Giorgi said she expected alcohol companies to do all they could to delay any further reform. She said a common tactic was to first introduce voluntary labelling, which was unclear and not widely applied, or to argue that any changes would be too difficult.

“Now that we’ve seen them implement pregnancy health warnings, we know that that argument is just incorrect,” she said.

“We also see alcohol companies change their labels all the time. The outcome of a football game can prompt alcohol companies to change their labels overnight.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article