Belfast ablaze: Fire crews get 203 calls for Twelfth of July bonfires

Fire crews receive more than 200 calls on first night of Twelfth of July loyalist bonfires across Belfast

- Hundreds of fires were lit across loyalist areas of Northern Ireland last night ahead of Twelfth of July parades

- Northern Ireland fire service said it received 203 emergency calls and responded to 98 operational incidents

- Twelfth parades, which are organised by the Orange Order, commemorate the Battle of the Boyne in 1690

Hundreds of bonfires were lit across loyalist areas of Northern Ireland last night as Protestant loyal orders prepared to celebrate the Twelfth of July.

Fire and rescue crews in Northern Ireland received a total of 203 emergency calls on the first night of celebrations to usher in the main date of the parading calendar.

As hundreds of bonfires were lit, Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service (NIFRS) responded to 98 operational incidents.

A spokesperson said there was a 12.5 per cent decrease in bonfire incidents compared to 2021, with the night’s activity reaching its peak between 11pm and 1am.

They added that between 6pm on Monday and 2am on Tuesday, 35 of the 98 operational incidents NIFRS responded to related to bonfires.

‘NIFRS maintained normal emergency response throughout the evening, attending a range of operational incidents including special service calls, a road traffic collision and other emergencies,’ the spokesperson said.

The Twelfth parades, which are organised by the Orange Order, commemorate the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

The battle, which unfolded at the Boyne river north of Dublin, saw Protestant King William of Orange defeat Catholic King James II to secure a Protestant line of succession to the British Crown.

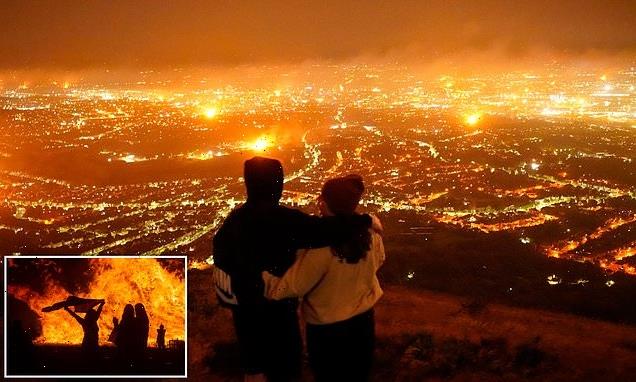

A view from Cavehill overlooking Belfast city of loyalist bonfires burning for the traditional Twelfth commemorations marking the anniversary of the Protestant King William’s victory over the Catholic King James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690

The Twelfth parades, organised by the Orange Order, commemorate the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 and will take place today

Pictured: Craigyhill loyalist bonfire in Larne, Co Antrim, on the ‘Eleventh night’ to usher in the Twelfth commemorations

A young man carries a Northern Ireland flag in silhouette past the burning Craigyhill loyalist bonfire in Larne, Co Antrim

Thousands of Orange lodge members parade through the summer months to mark William’s victory and other key dates in Protestant/unionist/loyalist culture.

Those celebrations culminate on the Twelfth – the anniversary of the Boyne encounter.

The routes of certain Orange parades became intense friction points during the Troubles, often leading to widespread rioting and violence.

The disputes usually centred on whether or not Orange lodges should be entitled to parade through nationalist areas.

While Orangemen insisted they had the right to parade on public roads following long-established traditional routes, nationalist residents protested at what they characterised as displays of sectarian triumphalism passing through their neighbourhoods.

The number of flashpoints has reduced significantly in the peace process years.

The build up to this year’s Twelfth has been low key and lacking the levels of tension and rancour associated with previous years.

On July 12, there will be 573 loyal order parades. Of these, 33 follow routes that are deemed to be sensitive.

Pictured: Craigyhill loyalist bonfire in Larne, Co Antrim, on the “Eleventh night” to usher in the Twelfth commemorations

Houses had windows boarded up and the fire crews hosed down properties to protect against the heat of the massive bonfire

Two men with drinks pose at the Craigyhill loyalist bonfire in Larne on the ‘Eleventh night’ to usher in the Twelfth celebrations

People celebrate as the Craigyhill bonfire burns in the Craigyhill housing estate, Larne County Antrim, Northern Ireland

A couple embrace in silhouette at Craigyhill loyalist bonfire on the ‘Eleventh night’ to usher in the Twelfth commemorations

A view from Cavehill overlooking Belfast city of loyalist bonfires burning as part of the traditional Twelfth commemorations marking the anniversary of the Protestant King William’s victory over the Catholic King James at the Battle of the Boyne

Pictured: Crowds of people celebrate as they watch fireworks at the Craigyhill bonfire in the Craigyhill housing estate

Fireworks are seen around the completed Craigyhill bonfire as it is set alight standing at 202.37208 ft, measured by an independent land survey company, aiming to break the world record of tallest bonfire, on the ‘eleventh night’

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) plan on the Twelfth being their busiest and most resource-intensive day of the year.

There will be 2,500 police officers on duty on the Twelfth, which is around a third of the strength of the PSNI.

The Eleventh Night is traditionally the Police Service of Northern Ireland’s (PSNI) second busiest and most resource-intensive day of the year.

Police said they were gathering evidence after receiving a number of complaints about election posters and effigies being placed on bonfires.

Earlier in the night, PSNI said there will be 2,500 police officers on duty on the Twelfth, which is around a third of the strength of the PSNI.

Monday night saw crowds gather across Northern Ireland to watch the towering pyres being set alight in loyalist areas, with the largest Eleventh Night bonfire taking place at the Craigyhill estate in Larne, Co Antrim.

But before the fires were lit, police said that they were investigating multiple reports of flags, effigies and election posters being placed on bonfires.

Hundreds of people watched on as the Craigyhill bonfire was lit at midnight with organisers confident that they had broken the world record for the tallest bonfire, after the pyre was measured at 202.3ft.

Nearby houses had their windows boarded up and the fire service hosed down properties to protect against the heat of the massive bonfire.

The build-up to the Eleventh Night celebrations was overshadowed by the death of a bonfire builder in Co Antrim on Saturday night.

Crowds celebrate as the Craigyhill bonfire burns in the Craigyhill housing estate, Larne County Antrim, Northern Ireland

People watch as the Craigyhill bonfire burns standing at 202.37208 ft, measured by an independent land survey company, aiming to break the world record of tallest bonfire, on the ‘Eleventh night’ in order to usher in the Twelfth of July celebrations

A view from Cavehill overlooking Belfast city of loyalist bonfires burning as part of the traditional Twelfth commemorations marking the anniversary of the Protestant King William’s victory over the Catholic King James at the Battle of the Boyne

John Steele, a window cleaner who was aged in his mid-30s, was killed when he fell from a separate bonfire in Larne that stood more than 50 feet tall.

In total more than 250 bonfires were constructed in loyalist neighbourhoods across Northern Ireland.

The fires are traditionally ignited on the eve of the Twelfth of July – a day when members of Protestant loyal orders parade to commemorate the Battle of Boyne in 1690.

The battle, which unfolded at the Boyne river north of Dublin, saw Protestant King William of Orange defeat Catholic King James II to secure a Protestant line of succession to the British Crown.

Most of the bonfires pass off every year without incident, but a number continue to be the source of controversy.

This year there have been a number of complaints from nationalist and cross-community politicians about their images being placed on the fires.

The SDLP’s Paul Doherty condemned those behind putting his election poster on a bonfire in west Belfast.

He said: ‘While I respect everyone’s right to celebrate their culture in their own way, we regularly see posters of nationalist representatives and hate speech on these bonfires and we need leaders in the unionist community to call it out and put a stop to it once and for all.

‘I have also heard concerns about the building of this bonfire so close to the local community centre and would ask those taking part to ensure that this bonfire passes off as safely as possible with no damage caused to the local community or surrounding areas.’

People Before Profit MLA Gerry Carroll said his election posters were also placed on the bonfire.

He said: ‘Unfortunately there has been a deafening silence from many unionist politicians in the face of this kind of sectarian intimidation.

‘It is time for leadership, and to demand an end to this provocation.’

Alliance Party MLA Stewart Dickson tweeted: ‘Saddened to see once again Alliance and other party election posters together with flags ranging from the EU to the Vatican and the Republic of Ireland on bonfires in East Antrim.’

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) tweeted: ‘The Police Service has received a number of complaints relating to flags, effigies, election posters and other emblems being placed on bonfires.

‘We are gathering evidence in respect of these complaints and will review to establish whether offences have been committed.’

Another fire lit at midnight was at Adam Street in the loyalist Tigers Bay area of north Belfast. Nationalist residents from the nearby New Lodge estate have previously claimed the fire is located too close to the interface between the two communities – something the bonfire builders have denied.

What is the Twelfth of July, why is it celebrated in Northern Ireland and why is it so controversial?

Huge bonfires will burn in loyalist areas across Northern Ireland late on Sunday night to usher in the main date in the Protestant loyal order parading season – the Twelfth of July.

– What is the Twelfth?

It is a day of commemorations, organised by loyal orders, marking the victory of Protestant King William of Orange over Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne, north of Dublin, in 1690 – a triumph that secured a Protestant line of succession to the British Crown.

The Orange Order, which was founded in 1795, continues to champion William’s legacy by espousing loyalty to the Crown and the Reformed faith. While the Orange Order is strongest in Northern Ireland, it does have a presence in Great Britain, the Irish Republic and many former British colonies.

Thousands of Orange lodge members parade through the summer months to celebrate William’s victory and other key dates in Protestant/unionist/loyalist culture. Those commemorations culminate on the Twelfth – the anniversary of the Boyne encounter.

– Why are bonfires lit the night before?

It has long been tradition to burn bonfires in loyalist neighbourhoods across Northern Ireland on the night of July 11 as a way of celebrating the upcoming Twelfth.

Most ‘Eleventh Night’ fires pass off without incident, with organisers promoting them as family-friendly community celebrations, but a number have become the source of controversy in recent years.

This year, because July 11 falls on a Sunday, several bonfires were lit early on Friday and Saturday night, but the majority will be ignited just after midnight on Sunday.

– What are the issues?

The problems are often centred on safety and environmental concerns within loyalist communities over the prospect of the towering pyres causing damage to homes and businesses.

Bonfire builders, most of whom are teenagers and young adults, have found themselves at loggerheads with the statutory authorities and, sometimes, older members of their own communities.

Police believe loyalist paramilitary elements also exert a malevolent influence in resisting efforts to relocate bonfires and restrict their size. Bonfire builders portray efforts to curtail the tradition as a veiled attack on their culture. Disorder has erupted in Belfast in the past when authorities moved in to remove material from bonfires constructed close to properties.

This year, the most contentious bonfire was erected in the loyalist Tiger’s Bay area, which is adjacent to the nationalist New Lodge area. Nationalist and republican politicians said that bonfires should not be situated near interface areas and claimed that residents had been subject to attacks on their homes by bonfire builders.

Two nationalist Stormont ministers, Nichola Mallon and Deirdre Hargey, secured the assistance of Belfast City Council to remove the pyre. But in order for BCC contractors to carry out the operation, they needed protection from the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). The police refused to do so, having made the assessment that an intervention would risk disorder, placing people congregating at the bonfire, including several children, at risk.

The ministers then launched a legal bid to try and force the police to assist in removing the bonfire, which was rejected in emergency High Court proceedings. Unionist politicians have said the Tiger’s Bay bonfire is smaller than in previous years and is a legitimate expression of their culture, and accused nationalist political leaders of raising tensions.

– Have the bonfires always been so big?

No. Eleventh Night fires were traditionally much smaller. There were also many more than there are today, with more numerous modest fires constructed on street corners across loyalist communities.

Over the years there has been a move towards consolidating the smaller fires into one central bonfire at the heart of each neighbourhood. This has partly been driven by a dwindling number of derelict sites for fires, but also by competitive rivalry among loyalist areas as to which can build the biggest bonfire.

– What is the problem around tyres?

While the bonfires are mainly constructed from wooden pallets, old tyres are often placed in the centre of the pyres as another fuel source. This is an ongoing source of controversy, with widespread concern, including within loyalist communities, on the health and environmental damage caused by torching noxious rubber.

Convincing young bonfire builders not to use tyres has often proved difficult. The problem has been exacerbated by suspicions that unscrupulous tyre dealers use the fires as a way to dump old tyres, avoiding the fees associated with conventional disposal methods.

– Why is the Twelfth so contentious?

Politics in Northern Ireland has long divided along traditional green and orange lines. Not surprisingly, the celebration of a historic battle fought on religious grounds is viewed very differently by the Protestant/unionist/loyalist and the Catholic/nationalist/republican communities in the region.

Older generations would contend the Twelfth was a non-contentious community event attended by Protestants and Catholics alike in the years before the Troubles. That changed markedly during the 30-year sectarian conflict that blighted Northern Ireland during the latter half of the 20th century.

The routes of certain Orange parades became a key friction point, often leading to widespread rioting and violence. While Orangemen insisted they had the right to parade on public roads following long-established traditional routes, residents in many nationalist neighbourhoods protested at what they characterised as displays of sectarian triumphalism passing through their areas.

– Are there other tensions?

The Northern Ireland Protocol, part of the Brexit deal, has aroused anger within unionist and loyalist communities. The Protocol introduced a new trading border to avoid the need for a hard border on the island of Ireland. This means that products being moved from Great Britain to Northern Ireland have to undergo EU import procedures at ports in Larne and Belfast.

Unionists say this damages trade and threatens Northern Ireland’s place in the UK. Earlier this year nearly 90 police officers were hurt after sporadic rioting linked to opposition to the Protocol broke out in several towns and cities in Northern Ireland.

There have been fears that heightened tensions around Eleventh Night bonfires could see a repeat of such scenes, although both unionist and nationalist politicians have called for the events to pass off peacefully.

Source: Read Full Article