It’s time to hasten slowly as rate cycle nears its end

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

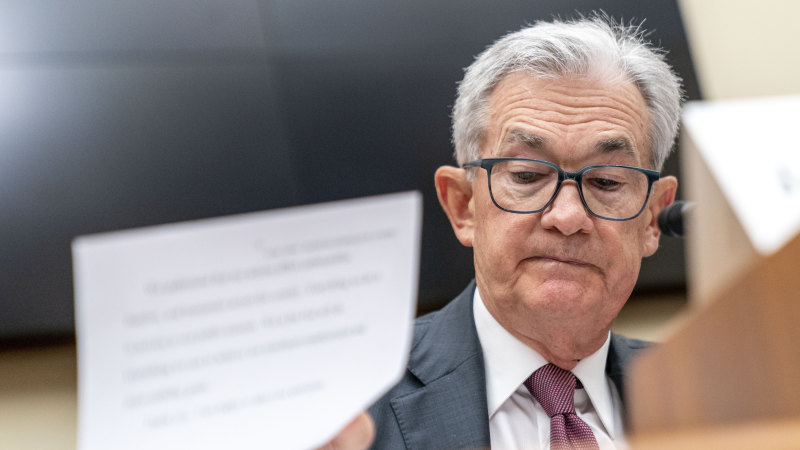

Jerome Powell’s testimony to the US Congress overnight confirmed what markets feared. The probability of two more official interest rate rises this year has increased.

The hopes raised by last week’s Federal Reserve Board decision to pause the most aggressive rate cycle in 40 years – a lift of five percentage points from 10 consecutive increases in 15 months – are fading, and this year’s strong sharemarket rebound is faltering as the likelihood of two more rate rises this year sinks in.

Powell told Congress that skipping a rate rise last week while flagging the potential for two more 25 basis point increases was consistent.

It’s not the speed of the rate rises that matters at this point, says Fed chair Jerome Powell.Credit: AP

“The level to which we raise rates is actually a separate question than the speed with which we move,” he said. “Earlier in the process, speed was very important. It is not very important now.”

While the headline US inflation rate has been dropping steadily, it remains high by historical standards at 4 per cent. “Core” inflation, which excludes fuel and food costs, has at 5.3 per cent proved even less responsive to the Fed’s rapid tightening of US monetary policy.

The Fed remains a long way off its inflation target of 2 per cent, hence the continuing “hawkish” tone of its commentary and rate projections.

Whether that 2 per cent target is the appropriate goal in unusual circumstances and peculiar economic settings is a continuing discussion.

Pandemic legacy

The stubbornly high inflation rates in most of the major advanced economies are a legacy of the pandemic and the various fiscal and monetary policy responses to it.

Massive supply chain disruptions that collided with surges in demand from households suddenly showered with government cash and experiencing near-zero borrowing costs ignited inflation rates that had been dormant for decades.

Global supply chains may now be functioning relatively normally, but they are changing amid the tensions between the US and its allies and China, the war in Ukraine and the lessons learned about the vulnerabilities created by over-reliance on global supply chains during the pandemic.

The restructuring of those supply chains, the push for re-shoring and friend-shoring of strategic production, will raise costs and have a continuing impact on inflation rates.

In that sense, the Fed and its peers are pushing against a tide that contains some unconventional factors. This not a conventional inflation cycle because it reflects, to some degree, structural changes occurring within the global economy that will play out over years, if not decades.

It’s also abnormal because, despite the rate at which the Fed and other major central banks have tightened their monetary settings, unemployment rates remain at or near historic lows, and the US economy has proved to be far more resilient in the face of the rate rises than expected.

‘Earlier in the process, speed was very important. It is not very important now.’

Sharemarkets, which ought to be rate-sensitive, have been on a tear over the past nine months despite the Fed and despite a surge in bond yields.

The big technology stocks, which ought to be the most rate sensitive, have led the charge, with the NYFANG index that includes all the US tech heavyweights rising about 70 per cent this year, heralding what might be another, AI-driven wave of economic change. Corporate earnings in the US and elsewhere are generally surprising on the upside.

The tools available to central banks are crude. They can raise the cost of borrowing and influence the amount of liquidity flowing within their financial systems.

There’s no doubt that, if they want to drive the inflation rate down to 2 per cent (in the Reserve Bank’s case, within a range of 2 to 3 per cent over time), they can.

However, given the economic conditions in the settings in the US and countries like Australia, that would come at a heavy cost in the form of household and business financial stress and distress, and a big spike in unemployment.

Arbitrary targets

The central banks’ targets are arbitrary. There’s no science to them, just a gut feel that 2 per cent, or the RBA’s 2 to 3 per cent range, is about right based on the central banks’ historical experiences.

When Paul Volker retired as the Fed’s governor in 1987 and was hailed as the man who broke the back of the last bout of ultra-high price growth, inflation in the US was around 4 per cent and no-one saw that as a threat.

It makes some sense for the Fed and other central banks to do what the Fed did last week and pause while waiting for more data.

There are long lags between central banks’ actions and their effects on real economies. It is only with hindsight – a year or 18 months later – that their success, or failure, can be evaluated.

Given how volatile, complex and largely unprecedented in the post-World War II environment today’s global economic and geopolitical circumstances are, hastening slowly makes even more sense.

It is conceivable, though probably unlikely, that the Fed and its peers have already done enough to bring their inflation rates down to acceptable levels (if not to their targets) without forcing their economies into unnecessary and avoidable recessions.

While the risks of inflation rates that are entrenched at unpalatably high levels are such that central banks will always err on the conservative side, the costs of over-kill are also significant. They shape people’s lives, and not in a good way.

Powell said that the two rate rises pencilled into its Open Market Committee members’ “dot plot,” or projections, last week were a “pretty good guess of what will happen” if the US economy evolves as they expect. Those members, and the financial markets, also expect rates to be falling next year.

Given that all the major central banks got it wrong during the pandemic when they believed the surge in inflation was “transitory,” those expectations have less credibility than they might once have had.

Whether they get it wrong by doing too much and inflicting avoidable damage on their economies, or too little and are forced to cause even more pain than they currently envisage, is, of course, the multi-trillion dollar question yet to be answered.

The probability of the central banks getting monetary policy perfectly right is, however, unlikely given their track records and the nature of the policy tools they have at their disposal.

Powell was right when he said that now speed is less important than the level to which rates are raised. What that level should be, however, remains an open – and for many threatening – question. Hopefully, the central bankers will err on the right side of caution.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article